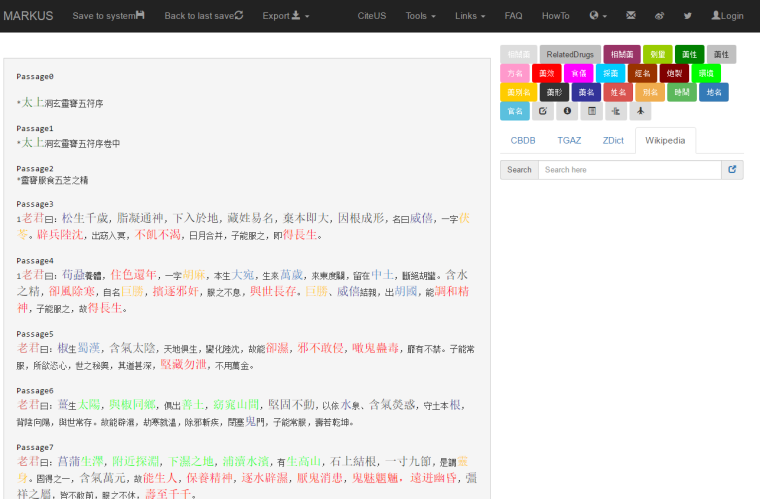

I use MARKUS as part of a project to data-mine the Daoist and Buddhist Canons for materia medica terms. I use MARKUS in concert with a team in Taipei at Dharma Drum Institute for the Liberal Arts (DILA) to mark up texts. Having selected my textual set, I then go through each juan that we have identified as important. I first mark up the drug terms using Keyword Markup. This then draws my eye to the “action” of the text. I then analyse how drug knowledge is being recorded in that particular juan, and mark up a sample passage for important related terms. These can include alternate drug names, place names, illness terms, anatomical terms and many more. By marking up the sample, I establish what I expect the ontology of the drug knowledge in that text to be. I then forward the text to the team members at DILA, who clean up the rest of the automatic tags and follow my lead to completely mark up that juan. Once I have checked their work we forward it to National Taiwan University for uploading into Docusky. (For more details on the other parts of the project please see here).

MARKUS is an exceptional tool for its ease of use and speed. We have budgeted that we can mark up roughly 16 juan per month, with one person doing it in Taipei. This means that over the course of a year, we can complete roughly 200 juan. This figure is very useful for project design and planning. Knowing this, we can analyse a set of texts and know roughly how long (and how much) it will take to get them marked up. Currently we are marking up Six Dynasties texts for drug terms and recipes. We can use our results at the end of a year to calculate how much and how long it would take to mark up the entire Buddhist and Daoist canons.

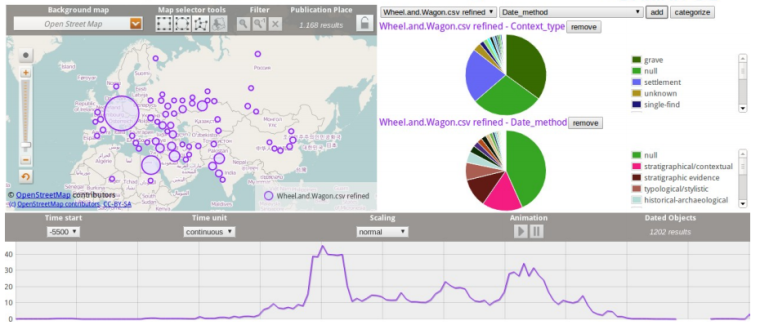

Once the marked-up texts are loaded into Docusky, we will be able to analyse them based on all kinds of criteria. Where do different communities source their materia medica? What sects use which drugs, and at what time in history? Can we see recipes moving across the corpuses? We will be able to do large-scale analysis in ways that have never been attempted before. We can plot relationship graphs to see how close the drug repertoires are. The exciting part about this is that we are not just trying out how to research materia medica. This method could be applied for any repertoire of terms that one wants to learn about – pantheons of deities, for example, or ritual objects and bodily cultivation practices. Finally, historians doing close readings of texts will no longer have to assume that their text is representative. They can do statistical analyses to establish at scale how representative the texts they use for close-up analysis are. So I feel that this is the beginning of a new digital methodology.

There are a number of directions where MARKUS could fruitfully grow to become even more useful, but it will require investment of time and resources to make these possible. For example, it would be a great benefit if we could draw relationships between the terms in a given paragraph or text. This is important not just for prosopography, but for detailed recipe analysis as well, as drug interaction is a fundamental part of recipe design in Chinese medicine. Right now, I cannot tell if two drug names in the same paragraph are alternate names for the same substance, working in parallel in the recipe, or are antagonistic to each other. We need to refine the tool to make these relationships visible.

Furthermore, it’s very important to be able to mark up textual layers in an easy and user-friendly way. Historical Chinese texts are always layered – whether it be commentary, or different editions that have been combined, or if the text is a composite of different hands that have been spliced together. Marking these layers is critical not only for analysing the contents of the text, but dating them. It would be extremely useful even just to publish digital editions where the different layers have been marked up, allowing others to do digital analysis of the different layers.

MARKUS is very well-suited for individual researchers, allowing one a lot of privacy, and even the ability to store files in the cloud. Allowing people to do this in a collaborative way would make it much easier for teams to work together. At present, it takes a bit of training and sending of texts back and forth by email to bring collaborators onto “the same page.” It would be very helpful if everyone could see “same page” live onscreen at the same time. Eventually, as our research in Chinese materia medica matures, I would like to work with colleagues and use MARKUS to compare textual corpuses from different languages, such as Sanskrit, Tibetan, Mongol, and Persian. We could see how close the drug repertoires were across languages, and whether or how recipes travelled. However, MARKUS needs more development to be able to search in those languages, as well as integration with stemming tools or other kinds of features to track terms with spelling variants, or as they undergo grammatical transformation. This would enable MARKUS to have a much broader reach, opening up possibilities for translingual digital research, making it a very powerful tool for the history of science or material culture. Done in concert with teams of philological experts from multiple regions, we could use MARKUS and good translation rules to link primary sources from different languages, and do research on the global history of medicine in an entirely new way.

MARKUS has changed the way I read texts, how I collect and organise them, and how I construct arguments about them. However, I feel it has much more potential to fulfil, and not just in Chinese studies. I look forward to future changes as more and more people recognise the usefulness of this tool. Well done Brent and Hilde.

Michael Stanley-Baker, Postdoctoral Fellow, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Dept. III

Citation Ho, Hou Ieong Brent, and Hilde De Weerdt. MARKUS. Text Analysis and Reading Platform. 2014- http://dh.chinese-empires.eu/beta/ Funded by the European Research Council and the Digging into Data Challenge.