LIU Jialong, PhD candidate in Leiden University

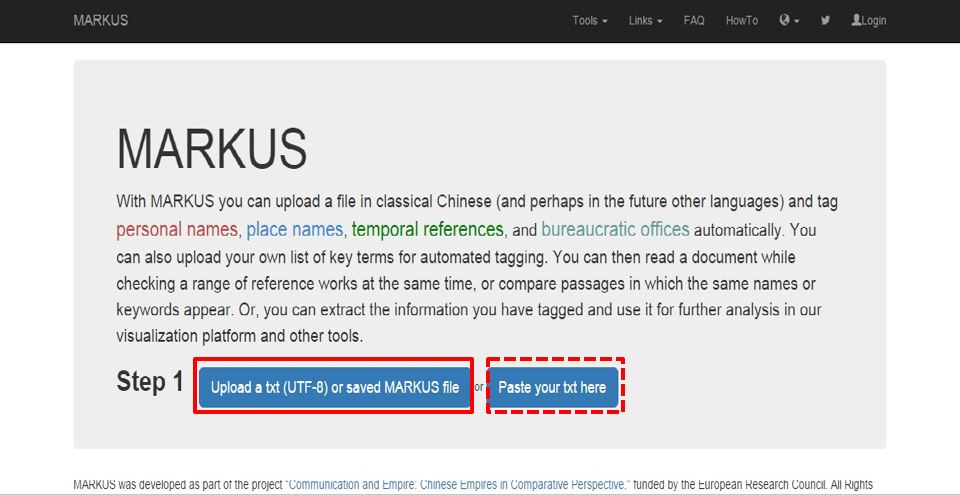

Ever since 2017, I have been participating in a project, chaired by Professor Hilde De Weerdt with the assistance of Xiong Huei-lan, the aim of which is to use digital approaches to investigate the history of construction in imperial China. We have selected the construction of city walls 城墻 to do a pilot study. In our research, an important step is to use MARKUS to mark up the information we want to analyze in local gazetteers (for a discussion of how to mark up and extract data with regular expressions in MARKUS, see Xiong Huei-lan’s post). The first step in this process is to identify and import or upload relevant primary source texts. In this post, I discuss where we can access relevant sources from local gazetteer databases.

Before acquiring texts from databases, we should evaluate them. It is necessary to be fully aware of the advantages and shortcomings of different databases. For example, how many gazetteers are included in a database? Can we browse the content of gazetteers? Can we download texts? Can we double check the original images in the database? What retrieval strategies are offered by a database? Does a database provide useful tools? In the following, I will briefly introduce select Chinese local gazetteer databases that are commonly used based on my own experience.

-

10,000 gazetteers will be included and 4000 of them are available

-

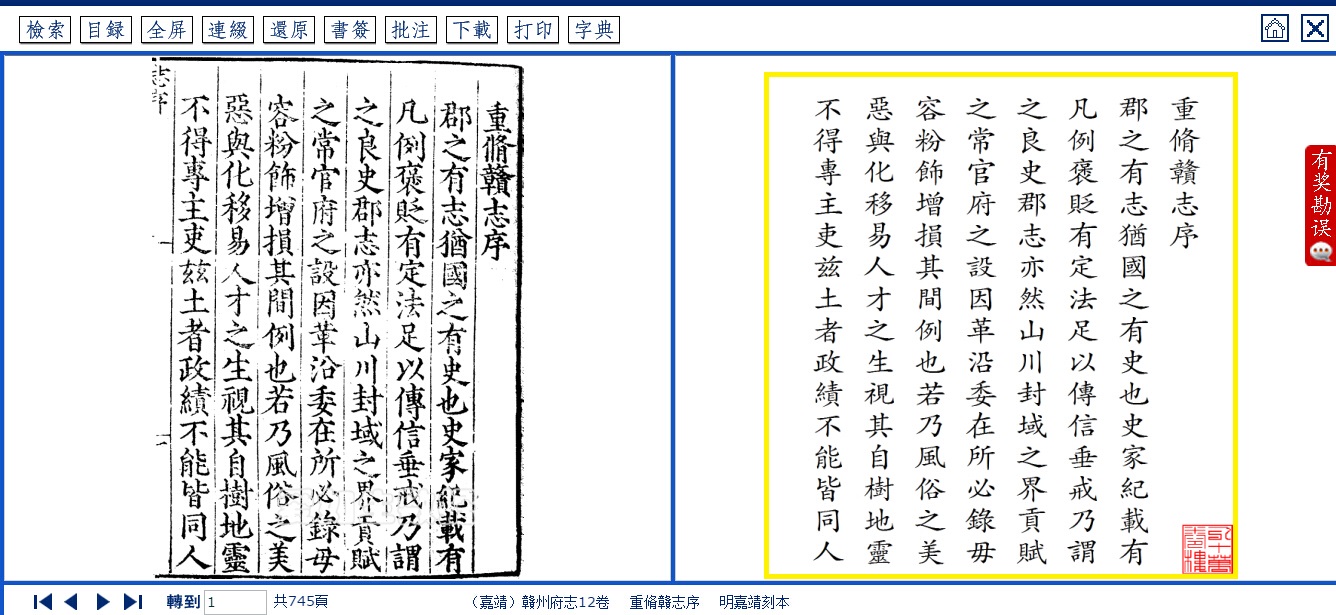

users can easily browse the content and compare the full text to original images of the titles included

-

texts can be download (to use MARKUS, save downloaded content as a .txt file)

-

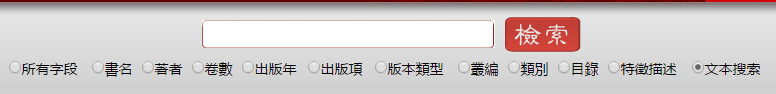

full-text retrieval is available

(2) Zhongguo shuzi fangzhiku 中國數字方志庫

-

11,000 gazetteers are included (This makes this the largest classical Chinese local gazetteer database I have used. Two examples: In the case of Chongming County 崇明, 中國數字方志庫 includes 6 gazetteers for different periods, whereas 中國方志庫 has 4. The latter misses two editions in 雍正 (1723-1735) and 民國 (1912-1949). In the case of Taicang Prefecture 太倉, 中國數字方志庫 has 8 gazetteers, whereas 中國方志庫 has 5. The latter misses two editions in 光緒 (1875-1908) and 宣統 (1909-1911), and an undated manuscript named 太倉衛志.)

-

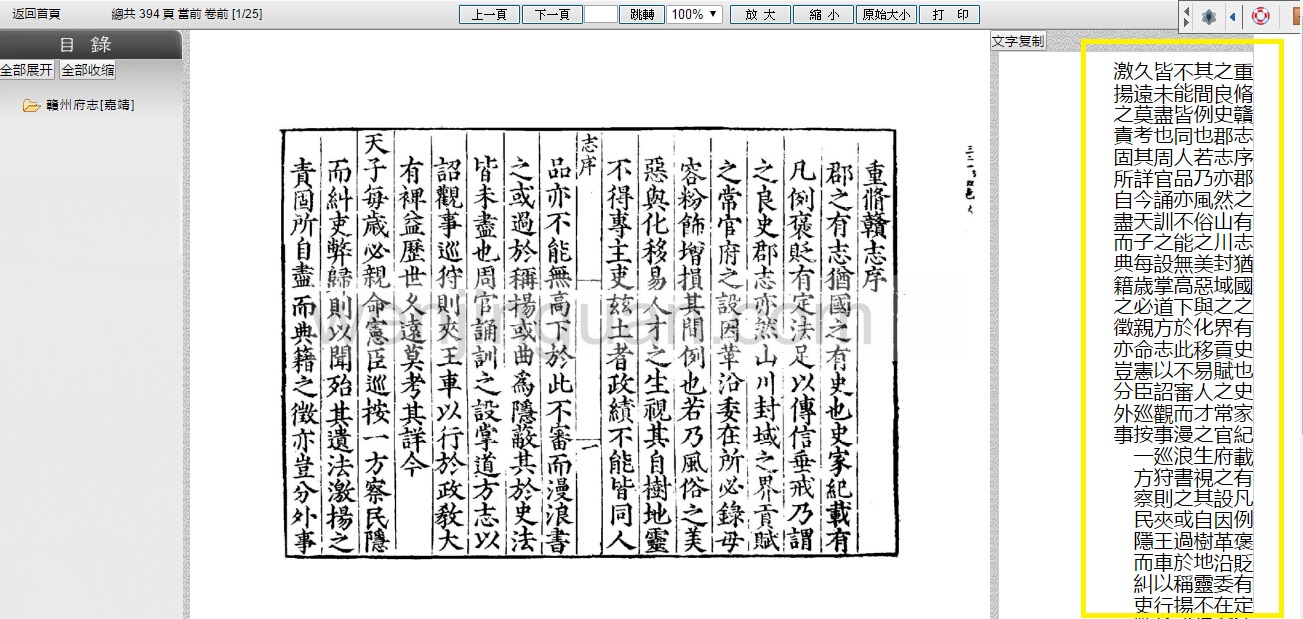

users can browse the content and have the access to original images of books

-

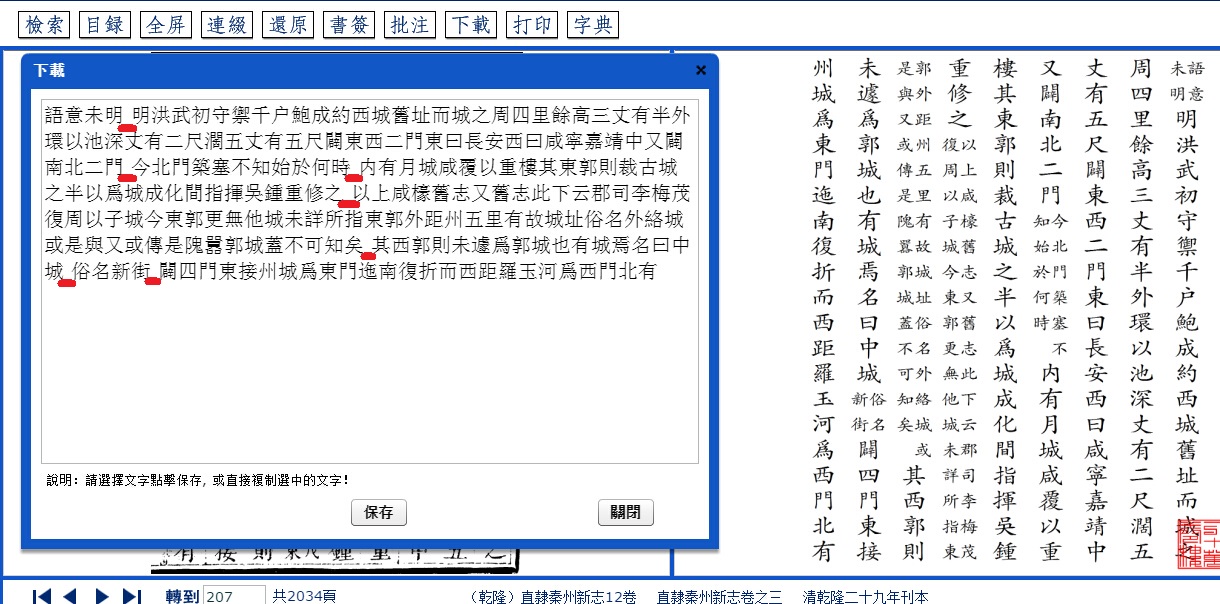

texts can be downloaded

-

full-text retrieval is available (However, users cannot search gazetteers based on region. By contrast, 中國方志庫 provides such a retrieval strategy.)

- the interface of 中國數字方志庫 is not as user-friendly as that of 中國方志庫, especially regarding the reading experience of the full text in font and layout

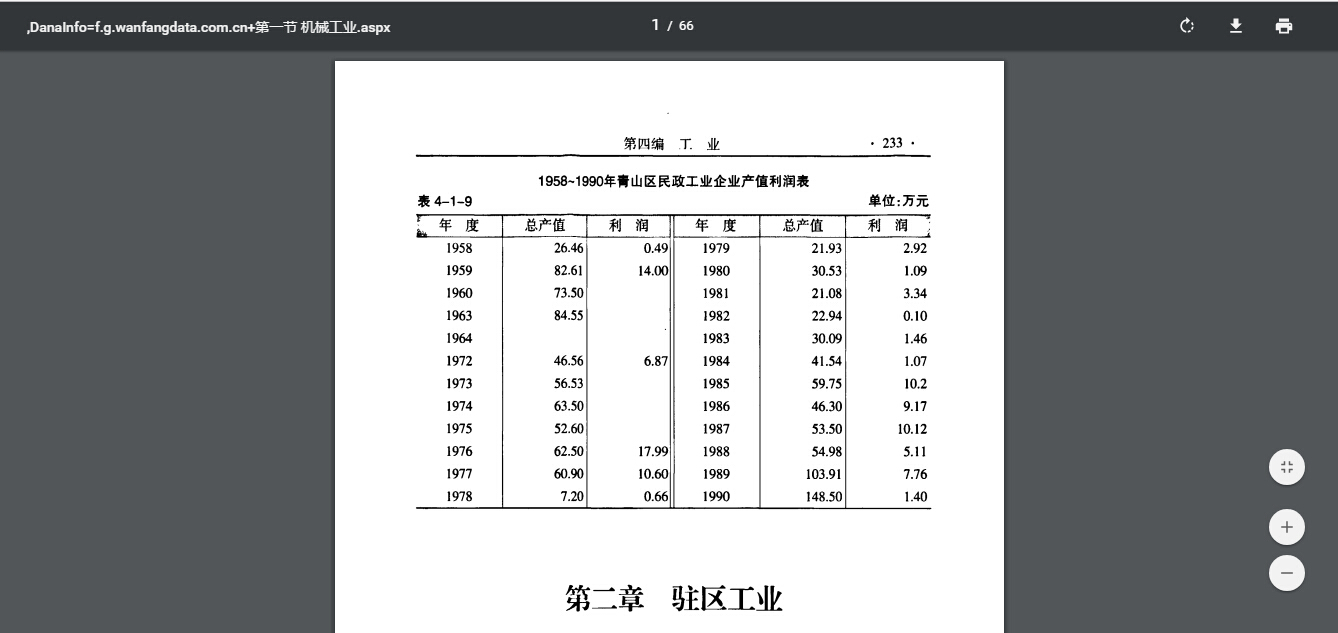

中國方志庫

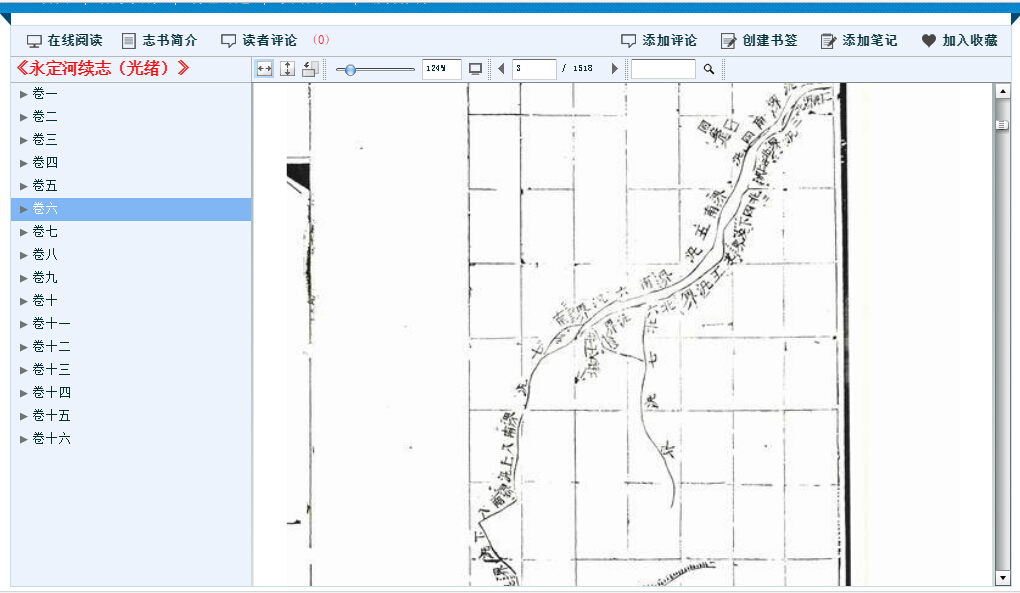

中國數字方志庫

(3) Xin fangzhi 新方志

-

40,000 gazetteers are included (It only covers gazetteers compiled after 1949.)

-

users can browse the content and directly read the original texts in PDF format

-

users can download the PDF files

-

full-text retrieval is impossible (search results are limited to chapters.)

-

includes 6000+ gazetteers compiled before the end of the Qing Dynasty held by the Chinese National Library

-

users can browse the content but the website often crashesusers can browse the content but the website often crashes

-

users can read the scanned images of gazetteers but cannot download texts

-

full-text retrieval is not available

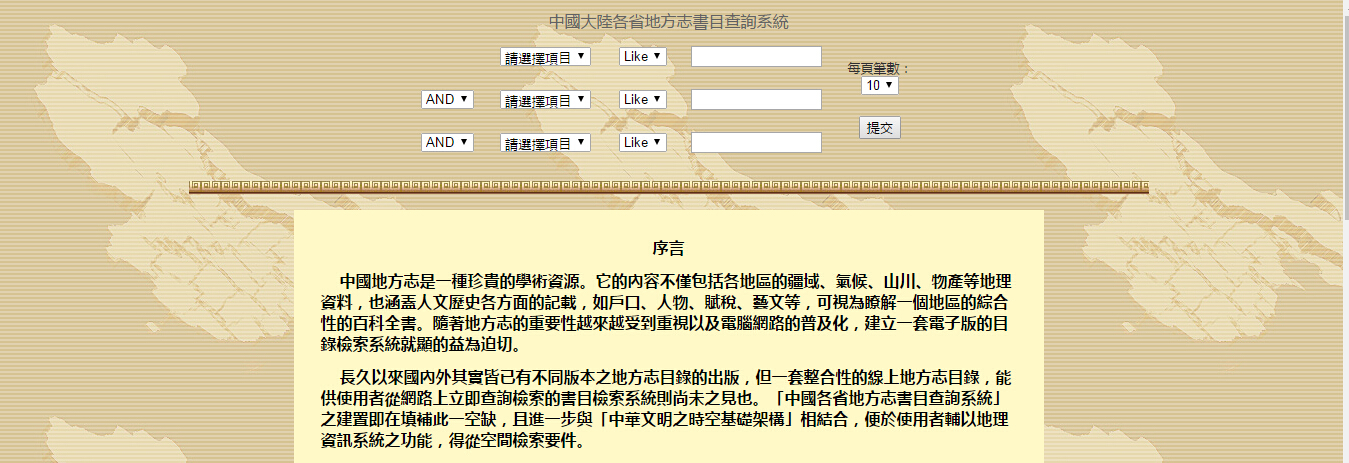

(5) Zhongguo dalu ge sheng difangzhi shumu chaxun xitong 中國大陸各省地方志書目查詢系統

-

a catalogue developed by Academia Sinica in Taiwan covering local gazetteers compiled both before and after 1949

-

users cannot browse the content of gazetteers

(6) Regional databases set up by regional libraries

This kind of database usually includes the local gazetteers in one region no matter when they were compiled. Below I use Beijingshi shuzi fangzhi guan 北京市數字方志館 as an example:

-

all the local gazetteers about Beijing are claimed to be included

-

PDF versions of gazetteers (scanned images of books) are offered online for users to browse

-

texts cannot be downloaded

-

full-text retrieval is unavailable

Before uploading texts acquired from databases to MARKUS, we should clean the digital text. When doing so, we should pay attention to blank spaces. In the texts acquired from 中國方志庫, blank space is used to indicate notes 注 in the original text. Such features can be used to, for example, mark up notes in MARKUS.

Variants of Chinese characters 異體字 should also be paid special attention to as they can influence the results of mark-up in MARKUS. I would advise to standardize all variants. If you cannot recognize a variant of a character, you can refer to the dictionary provided by 中國方志庫 or a professional online dictionary for variants specifically, 異體字字典 . (Xiong Huei-lan also describes the difficulty caused by variants when using regular expressions in her post.)

Depending on the quality of the OCR, there may be missing characters or wrong characters in the texts you acquired from electronic databases. When cleaning the text, such problems should be addressed. After cleaning your texts, upload them to MARKUS and explore them with the variety of functionality provided by the platform.